What does it feel like to have a body?

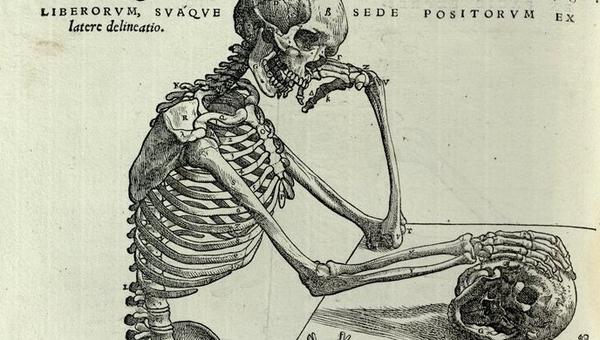

In his seminal work Bodies and Selves in Early Modern England, Michael Schoenfeldt explores the impact of humoral theory on this question in the writings of early modern English authors like Donne, Spenser, and Herbert. In the first chapter of the book Schoenfeldt ponders the continuing attraction of these physical descriptions, even though the scientific theory (that is, of bodily “humors” constituting the self) has been left behind. He writes,

Humoral theory is not the dry recounting of Aristotle or Galen that it is often construed to be… but rather a remarkable blend of textual authority and a near-poetic vocabulary of felt corporeal experience.

Indeed, when one gets over the initial unfamiliarity of a particular description of a bodily process, one is struck by the fact that this is indeed how bodies feel as if they are behaving. So different from our own counterintuitive but more effective therapies, these accounts describe not so much the actual workings of the body as the experience of the body. (p.3)

“The experience of the body.” When reading early modern literature, in other words, one can find a surprising glimpse of recognition. That is what indigestion feels like; that is what sleepiness feels like; that is the feeling right before breakfast. The explanations for these processes, and the words used to describe the experience, are foreign and out-of-date; given this, we can be shocked by the closeness, the startling intimacy of the way these men and women represent corporeality. [1]

We can be fairly comfortable with going back into the archives to find literature that speaks to our present emotional experience. When you’re in love, go to Shakespeare’s Sonnets; when you lose someone, go to Donne’s meditations on death and grieving. People have done this for generations, finding in long-dead words what Alan Bennett described in The History Boys, “And it is as if a hand has come out and taken yours.”

What Schoenfeldt pointed out in the passage quoted above is that this recognition, Bennett’s hand-taking, can apply to experiences (like that of the body) which on the surface seem to be disconnected from contemporary life. Despite medical and scientific advances, the way that people in 16th- and 17th-century England imagined their bodies can be just as recognizable, just as oddly familiar to us in the present day.

So what does this have to do with digital experience?

If, Sherry Turkle noted in Alone Together (2011), “Technology reshapes the landscape of our emotional lives,” then there remains a need for describing that new landscape, for navigating the inner terra incognita created by our connected selves. I’m fascinated by the terms that emerge (“ghosting” comes to mind; Aziz Ansari’s description of waiting for the magical ellipsis on iMessage when your crush is texting you back) to articulate the phenomenon of digital life.

New phrases, even new technical words are required for new experiences. George Herbert didn’t have a metaphor for being addicted to your iPhone.

But Turkle’s phrase in the quote above is illuminating, as are her more extensive writings elsewhere. Technology reshapes the way we feel, re-categorizes, re-forms. It brings into new arrangement the same ingredients — desire, jealousy, fear, anger, love — which have made up human experience for a very long time.

Schoenfeldt’s observations about humoral theory have suggested a parallel to me: perhaps the same corpus of early modern literature could provide signposts in navigating our “new landscape.” I wondered would happen if I considered the poetry, drama and scattered prose, looking for answers to the question,

What does it feel like to have a digital life?

This anachronistic impulse probably stems from a generational interest in pastiche. At the Oxford PROGRESS graduate conference in June, I heard a fantastic talk by Claire Spears on the history and increasing significance of GIFs in the way we communicate. Claire highlighted beautifully the contrast between what is said in a GIF (the category or tag) and what the moving image refers to (say, a Kardashian moment.)

Perhaps especially as millennials, we draw meaning from contrast, from unexpected coincidences of cultural artifacts. Those coincidences are usually, as Claire pointed out, between elements of low-brow pop culture which are commonly known.

But what if, instead of using Keeping Up with the Kardashians as our corpus of cultural reference, one looked to early modern literature? What would I find?

There are some reasons to think about the early modern period specifically in regards to digital transformation, given the somewhat analogous technological change many experienced in the 16th and 17th centuries. (William Powers’ chapter on Hamlet in Hamlet’s Blackberry is particularly illuminating if you’re looking for a place to start.)

But for me, this literature is the body of work I’ve been studying for several years, the one I’ve fallen in love with and find impossible to set aside. I’ve been thinking about these connections between Renaissance literature and the experience of digital life for a few years, since reading Hamlet’s Blackberry. I attempted to make a few connections of my own in a paper I gave at PROGRESS. Over the next few weeks, and in addition to other musings, I’ll explore case studies of early modern writers and digital phenomenology.

Until then, friends.

***

[1] It perhaps goes without saying that this preliminary observation is by no means the only claim of Schoenfeldt’s influential study; if you’re a fan of great writing about great authors, check it out.